Is Pidgin the Firefox of IM?

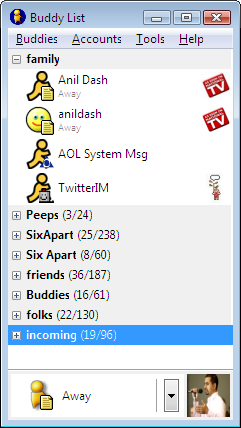

Pidgin, formerly GAIM, is the best instant messaging client available; It works with all common IM networks, supports extensions and customizations through plugins, has smart and simple default settings, runs on all common desktop platforms, and is a free open source application. Being so similar to Firefox in so many ways, this leaves the application poised to become the “Firefox of IM”.

Pidgin has a somewhat complex history. Originally named “GTK+ AOL Instant Messenger” after the network it was designed to connect to and the window UI toolkit (!) that it used to display itself, the name of the application has been in flux for years due to legal posturing from AOL. In the intermediate years, the name became somewhat anachronistic anyway, as the application added support for MSN, Yahoo, ICQ, Jabber, and other chat services in addition to AOL’s AIM service.

Now, the last time an essential open source internet client shed its geeky name in favor of one that was more approachable, Phoenix became Firebird and later Firefox. The evolution of the naming of these clients doesn’t just reflect the incessant legal sniping over IP and branding that a lot of small projects face, but is also a measure of a focus on the image of the projects. This is somewhat atypical for a lot of open source projects, as some contributors can see a focus on branding as irrelevant to, or even contradictory to, making a good product. But while the Pidgin site lacks some of the slickness and polish of the Firefox site, it’s still miles better than the standard “choose a SourceForge mirror for your tarball”-style experience that a lot of comparable projects present to the world.

The renaming to Pidgin also reflects the 2.0 release of the program, a significant milestone that reflects a modularization of the application’s underlying architecture, as well as support for additional communications networks. But of course, there are other applications which support each of Pidgin’s features, including the clients created by the IM services themselves. Even other third-party clients, like Trillian, support a range of networks as well as many more features than Pidgin includes out of the box.

But where Pidgin’s UI is spare, even underdesigned, Trillian commits errors such as the worst default preference setting in the history of modern computer software, a misfeature which automatically links some terms in your conversation to Wikipedia articles. With competition that’s trying to pass regular expression stunts off as user benefits, it’s no wonder that Pidgin’s simplicity seems like a breath of fresh air.

And if you want that sort of complexity, there’s a very healthy ecosystem of third-party plugins and extensions to customize Pidgin. Many of them are oriented around practical needs like deeper integration with Windows than is possible with a generic cross-platform client.

In short, the parallels between Firefox and the new Pidgin are undeniable. In a field crowded with proprietary, confusing clients that are tied to individual networks, Pidgin reflects the reality that all of us are connected to more than one network. And despite the rush to try to convert all desktop applications into Ajax-powered web equivalents, there is still ample proof from Firefox’s example that powerful, smart, extensible desktop applications are an essential part of the Internet’s evolution as well.

All that remains to be seen is if Pidgin will succeed in capturing attention and inspiring innovation in the same manner as its open source sibling.